If Only My Parents Knew This

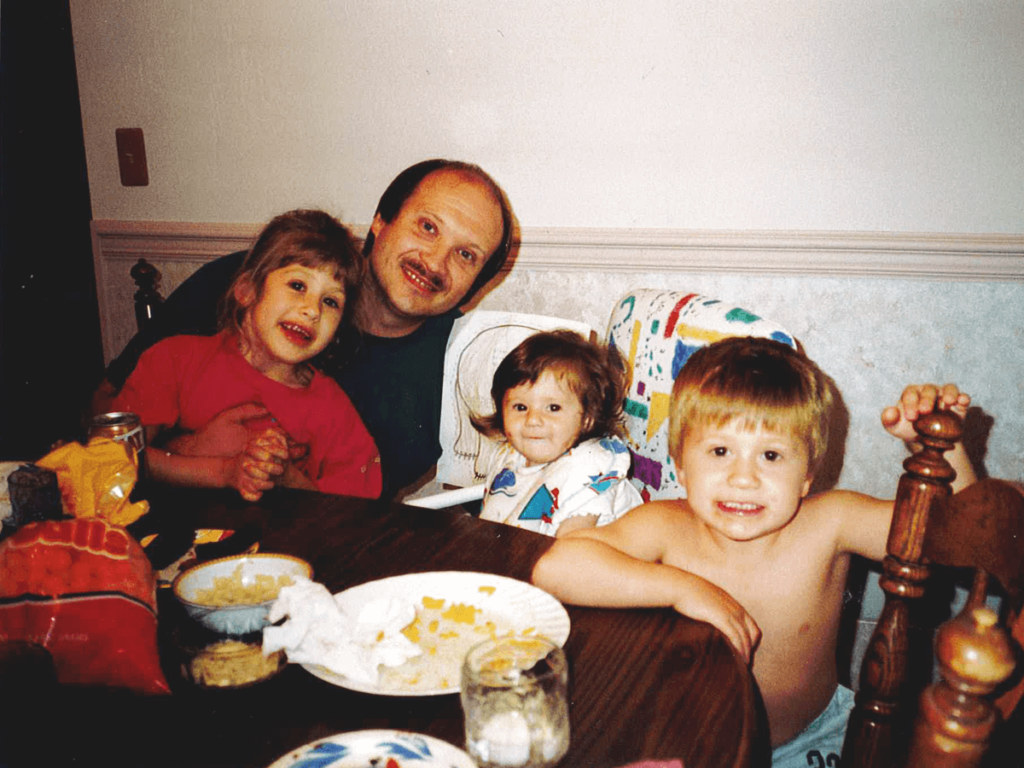

My mom and dad raised three children.

My sister, Lauren, was the first-born, and then came my brother, Aaron, and lastly, me. My sister has Asperger’s Syndrome, which is a high functioning form of autism, diagnosed at the age of four.

Like any daughter, there are things I wished my parents did differently.

I wished they never got a divorce, I wished they worked together instead of spent their days fighting, and I wished they were able to take a step back from autism so that they could evaluate our circumstances without being lost in the emotion of it.

Autism is a huge part of all of our lives.

It’s the embarrassing scenarios that run through my head when someone mentions they saw my sister out in public. It’s the aching pain I feel when I read about an injustice towards a special needs individual. It’s the strangers who flooded my home over the years, all with the same promise to improve my sister’s social deficiencies.

This post has nothing to do with my parents. It’s not an evaluation on the areas where they fell short. Rather, I hope it serves as inspiration for the parents who are actively raising both neurotypical and neurodiverse children.

As a child, I had difficulty articulating my needs. I was growing up in the shadow of my sister, whose syndrome necessitated most of my parents’ time and energy.

Now as an adult, I want to be there for other neurotypical siblings on the same journey.

So parents, if you’re listening. This is what I’d like you to know.

I wanted to know more about Lauren’s diagnosis.

Explain the reward system that is working for her and why she gets a quarter each time she showers when I do that for free. Read me her social stories so that I can understand her emotional capabilities. Tell me the smallest details she has to learn like how to pause during a conversation to allow the other person a turn to speak.

At times, I thought Lauren was better off than other special needs kids, but that is because I did not grasp the whole of her complex neurodevelopment disability.

I think my parents wanted me to retain some sort of childhood innocence as the last born, but when it comes to family, autism isn’t a closed-door experience.

It is an in-your-face, leave-the-movie-early, affect-everyone-around-you type of syndrome.

I was never going to be able to play the role of Lauren’s little sister, so why be treated like one?

I wanted my sister and me to be treated equally.

If Lauren was angry about what television show I put on then I’d have to leave the room so she could calm down.

If Lauren left period blood all over the toilet, someone else would clean it off for her.

If Lauren called me a brat, slut, or told me that I was ugly; there was no consequence to curb her inappropriate behavior.

While I was expected to control my emotions, clean up after myself, and not use foul language, the standard fluctuated for my sister.

This was one of the most aggravating aspects about growing up alongside autism. There was some structure, but not enough.

There were family therapy sessions, but no long-term solutions.

I needed my parents to come up with a plan that was conducive to both of our understandings of the house rules and then enforce them.

It was easy for me to see my parents’ leniency on Lauren as a reflection of my own worth.

If they cared about me then they would care about the rules too.

Fixing Lauren and mine’s relationship needed to become a priority.

Over the last few years, I discovered Lauren’s behavioral plans and was shocked to find that though the years changed, most of her goals remained the same.

She still needed help completing her ADL’s, identifying and expressing her feelings, and learning how to be more comfortable with overwhelming stimuli.

In childhood, I can remember sitting at my wooden dining room table, both my family and the BSC present. We’d discuss Lauren and mine’s issues, but it seemed that our relationship never became a priority.

On one hand, I get it. Having a good relationship with your sister may not seem as important as maintaining eye contact or learning to change your underwear after a shower. It’s not as important as learning to write legibly or developing social skills in structured and non-structured settings.

But it should be.

At the lowest point in our relationship, Lauren refused to sit next to me.

There was name-calling and throwing plates. We behaved like enemies.

I know my parents had a lot to deal with, but I needed them to help us. To help us grow closer and understand that our relationship is a precious, fragile thing.

I needed to go at my own pace.

I was embarrassed…

When Lauren peed her pants in Staples.

How she’d ask, “Who are you?” to anyone that knocked on our front door.

Or if she threw a tantrum in the Walmart checkout line.

I didn’t like to have friends over my house or invite my sister to my soccer games. I didn’t feel comfortable being associated with Lauren.

This was something that took me years to navigate and the truth is I am still learning how to be less self-conscious with Lauren around others.

I would have benefited from better coping skills, but I also needed my parents to take me by the hand and walk me through being a sibling to someone with Asperger’s.

To learn how to embrace both the good and bad of this season while understanding my own boundaries or triggers.

When it comes down to it, our parents are going through a lot, balancing the varying needs of their children.

My advice to you reading this is to take time for your neurotypical child too.

Give them your attention after you get off of that hours-long phone call trying to make an appointment with yet another specialist. Sit down with them after the therapist leaves to let them know that you are on their side. And take them out to eat alone, checking up on what’s going on in their life.

Because we just want to know that our parents care, that they are fighting for us too.

Written by, Jenna Kapes

Jenna Kapes is passionate about de-stigmatizing the sibling experience and runs her own blog at The Sibling Diary. She works for her local intermediate unit and is currently seeking representation for her debut memoir, titled, Flipping the Behavioral Plan: A Sibling’s Perspective on Asperger’s

Interested in writing for Finding Cooper’s Voice? LEARN MORE

Finding Cooper’s Voice is a safe, humorous, caring and honest place where you can celebrate the unique challenges of parenting a special needs child. Because you’re never alone in the struggles you face. And once you find your people, your allies, your village….all the challenges and struggles will seem just a little bit easier. Welcome to our journey. You can also follow us on Facebook, subscribe for exclusive videos, and subscribe to our newsletter.