Understanding Different Approaches for Emotional Regulation

One thing I’ve learned in my work with children and families across the globe is that no two families or children are alike. Every time I think I have the secret sauce for helping a tantrum-prone child with autism in Germany, Japan, Texas, or Ontario, I’m humbled by the reality that what works well for one family may fail miserably for another.

Over many years of clinical work at Boston Children’s Hospital and in private practice, I’ve come to the conclusion that a “one size fits all” approach simply doesn’t exist.

Nevertheless, there are several creative ways to help children who struggle with emotional regulation.

Our traditional clinical model for teaching kids how to cope with BIG emotions is very complex. I’ll use a story from one of my clients, Jenny,* to illustrate this point. Here’s how Jenny described a recent breakthrough:

“Last week I didn’t hit my brother when he stole my toy. I felt myself getting really mad because he took my bunny, Ben. I was ‘in the red’ I was so mad. But the last time I got angry and hit him, I got into really big trouble. I took some deep breaths and talked to my mom about it. I didn’t get into trouble and I had a good day. We even got ice cream later.”

You might be thinking, “Isn’t that what all kids are supposed to do that in situation?” Ideally, yes.

That said, Jenny’s reaction encompassed a complicated series of steps that even many adults struggle to accomplish: She felt her body become agitated, identified a pattern that had gotten her into trouble before, and stopped herself in time to find a different path. She was able to recognize the emotion of anger, label it, and even give it a color. She then, amazingly, recalled a skill she had learned—deep breathing—and used it to calm her anger.

She also exhibited some pretty powerful processing skills in that she approached her mother and reached out for support instead of withdrawing or retreating.

It’s easy to imagine Jenny dealing with her brother’s behavior in a less reasonable, more impulsive manner.

The equation brother steals toy = I hit him is fairly intuitive.

On the other hand, the equation brother steals toy + I get mad + I realize my mad is ‘red’ + I don’t want to get into trouble + I use a coping skill + I talk to my mom about it = not in trouble + good day + ice cream is significantly more complex and not something most kids can grasp.

To use a metaphor, we often ask our kids to do algebra but call it simple math. What about the kids who don’t understand when they’re getting upset, who don’t know how their body feels when they’re agitated, who forget their coping skills?

A patient of mine, Greg,* is one of those kids.

Greg is a very smart boy who excels in science and technology. He also lacks impulse control and has a very active body. Some might diagnosis him with ADHD or suggest he has sensory processing issues. Others might give him a diagnosis of autism.

He struggles to connect to peers and does not like hugs. He bonds with adults over highly complicated games and scientific knowledge. He is lovable and engaging, but when he’s frustrated, his outbursts can be very extreme (e.g., jumping off furniture, yelling at people, ripping up papers).

While many teachers, therapists and providers had attempted to teach Greg some strategies for managing his extreme emotions, nothing seemed to stick. His frustration hit so hard and fast that there was little room to intervene.

The more drastic his behaviors, the larger the consequences and the more powerless the adults who loved him felt they could be to help him. The simple math equation wasn’t working, and the algebraic one was far too complex.

Working with Greg, I realized that the issue wasn’t his failing to learn how to calm himself down—it was our failing to find the right way to help him.

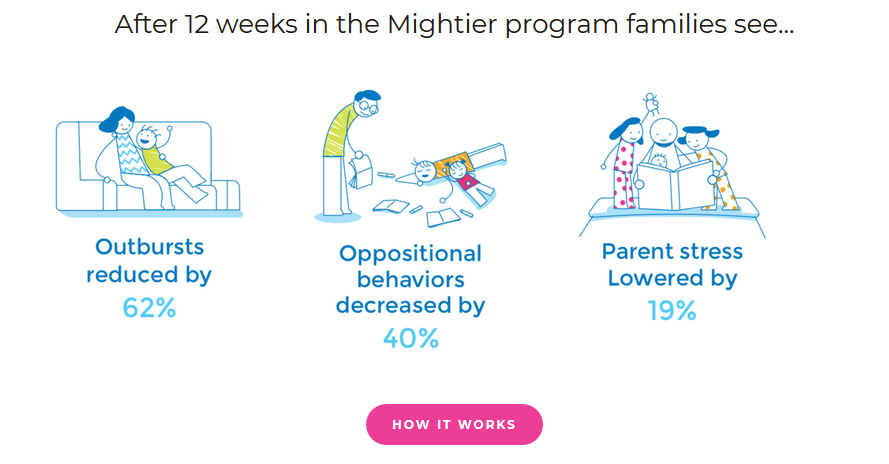

After trying a few different approaches with Greg, I introduced him to a bioresponsive program called Mightier, mainly just to see if he liked it and if it had any sort of effect on the frequency, duration, or severity of his episodes. (Disclosure: I am the Clinical Services Director and VP of Parent Services at Mightier.)

Bioresponsive technologies like Mightier give children immediate feedback on their biological responses and reward them for calming their bodies and heart rates. The first time Greg used Mightier, he wore a heart rate monitor (like a watch) and played a series of video games.

As his heart rate rose, the games became more difficult to play. He learned very quickly that he would have to stay calm, cool, and collected to have success in the games.

In bioresponsive technology, there’s no judgement, discussion of feelings, or additional processing. Best of all, there’s no concerned adult creating algebra when simple math will do: control of heart rate = success.

Greg quickly figured out his own unique technique to lower his heart rate (thinking about his favorite animal) and mastered his heart rate in spite of greater in-game challenges. Within a few short weeks this automatic heart rate control was transferring outside of the games as well. Teachers saw him take a pause to calm himself instead of taking his frustration out on school supplies. His outbursts remained, but there was a subtle shift in severity and frequency.

In six weeks, he had demonstrated measurable changes on several of his Individualized Education Program goals. Greg taught me the power of simple math.

Another boy, Tim,* helped me learn that sometimes kids need to have a visual connection in order to put their emotional regulation skills to use. Tim is a 12-year-old diagnosed with autism, ADHD, auditory processing disorder, and anxiety. Even though his family used a variety of tools and resources, they realized something was missing.

“He had a lot of skills and he would use these tools, but things weren’t naturally kicking in for him,” his mom said. Similar to Greg’s case, Tim’s mom wondered if he could benefit from bioresponsive tools and a way to “see” his body in order to make changes.

After Tim had been using Mightier for a few weeks, his mom noticed significant changes in his behavior at home and in school. Up to that point, he had experienced “dozens” of outbursts in school.

Once he started playing Mightier games, his outbursts dropped down to three for the entire school year. Most importantly, his mom said, Tim himself noticed a difference. He began asking to use Mightier when he felt stressed. He even had the idea of taking Mightier with him on the school bus.

Previously, he had experienced a large portion of his stress on the way to school, which colored the rest of his day. When he played Mightier games on the bus, he could see his heart rate and bring it down before getting to school. This helped him remain calm throughout the day.

Tim’s family had years of practice with various social and emotional regulation strategies. All of these worked, to a degree. For this particular child and this particular family, though, bioresponsive therapy was the key to translating many of these other models into real life.

Tim’s mom said it herself: “The tools we used didn’t help Tim make the connection between his mind and body. Mightier tells you, ‘This is your body and you can control it. You can control your breathing and your heart rate.’ He never had a visual for this before the Mightier program.”

Since working with Greg and Tim, I’ve tried to help kids think about their “calm-down behavior” in creative, less traditional ways. We talk about heart rate as a proxy for emotions: “Feel your heart? Can you elevate it? Decrease it?” This takes away the noise and all the processing that surrounds identifying feelings, triggers, and coping skills. I try to strip the emotion (mine and that of other adults) out of these interactions as I’ve recognized that kids are often far more sensitive than we think.

I ask myself, “What resonates for the child? How can we empower the kiddo to have success in the simplest way, even when I’m not around?” Since most kids don’t like feeling upset and out of control, we can use their motivation to find a solution. When they see a little success in body control, they become greedy for more.

There is no one “right” way to learn emotional control. The more I work with kids who think differently, the more creative I become in my approaches and the more willing I am to challenge the status quo. I am humbled daily.

These kids have taught me that some of our tried and true methods for self-regulation don’t take into account the development of automatic emotional muscle memory. The steps required to calm down take too long. It’s like asking a child to learn to ride a bike by reading a manual when we all know that the best way to learn is to practice (and to fall down a few times). Or learning a foreign language from a textbook rather than an immersive experience.

Stripping away the absolutes and allowing freedom for different ways, different kids, and different processes has made me a better therapist. I thought I was teaching them, but really, the kids are teaching me.

We’re all in this together, to create a better, more tolerant, and more supportive society.

The second I stopped making it about “my way or the highway,” the highway became a lot easier to navigate.

Written by, By Dr. Erina White

*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals.

Erina White, PhD, MPH, MSW is the Clinical Services Director and VP of Parent Services for Mightier. She is a clinical researcher at Boston Children’s Hospital, therapist in private practice, and holds faculty appointments at Harvard Medical School, University of New Hampshire and Simmons School of Social Work. She is also a mom. Mightier uses the power of bioresponsive games to help kids build and practice calming skills to meet real-world challenges. To learn more more about Mightier, and how they are helping children learn to succeed by staying calm, click HERE.

Interested in writing for Finding Cooper’s Voice? LEARN MORE

Finding Cooper’s Voice is a safe, humorous, caring and honest place where you can celebrate the unique challenges of parenting a special needs child. Because you’re never alone in the struggles you face. And once you find your people, your allies, your village….all the challenges and struggles will seem just a little bit easier. Welcome to our journey. You can also follow us on Facebook and subscribe to our newsletter.